All the Rules of Heaven Read online

Table of Contents

Blurb

Dedication

Author’s Note

For the Sake of Momentum

Blind Faith

Not-Damie. Also, Not-a-god

Don’t Touch That, Dammit!

Soul Voyeur

The Shape of the Thing

Seen

Ghostbusting a Nut

Gateway

Let the Healing Begin

Once More into the Breach

Spilled Like Wine

Blurred Letters

Blood

Innocent

I Know You

Can’t Find My Way Home

Stay

Broken Glass

Dark Moon

Monsters

The Unsullied Souls of Men

Promises of Recovery

More from Amy Lane

Reviews

About the Author

By Amy Lane

Visit DSP Publications

Copyright

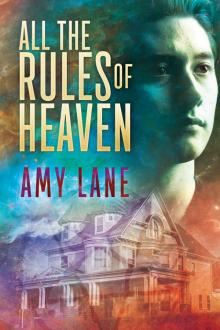

All the Rules of Heaven

By Amy Lane

All That Heaven Will Allow: Book One

When Tucker Henderson inherits Daisy Place, he’s pretty sure it’s not a windfall—everything in his life has come with strings attached. He’s prepared to do his bit to satisfy the supernatural forces in the old house, but he refuses to be all sweetness and light about it.

Angel was sort of hoping for sweetness and light.

Trapped at Daisy Place for over fifty years, Angel hasn’t always been kind to the humans who have helped him in his duty of guiding spirits to the beyond. When Tucker shows up, Angel vows to be more accommodating, but Tucker’s layers of cynicism and apparent selfishness don’t make it easy.

Can Tucker work with a gender-bending, shape-shifting irritant, and can Angel retain his divine intentions when his heart proves all too human?

Mate and the kids—check. And Mary, for being there—but this book wasn’t her favorite. So this book is sort of dedicated to me—it was written to please me, and while nobody else may love it, I know I do.

Author’s Note

For those of you interested in the fairy hill Tucker mentions, by all means check out my Little Goddess stories. In real life, Foresthill is a teeny community. In Amy’s land, there are more things in heaven and earth….

For the Sake of Momentum

THE BED that dominated the center of the room was hand-carved, imported ebony, black as night, and the newel posts had been studded with an ivory inlay, random designs supposedly, dancing around and around in a way that made the unwary stop, lost in the intricacy of runes nobody living could read.

The wallpaper had once been an English garden jungle—cabbage roses, lilacs, mums—riotous around the walls, and the grand window was positioned strategically to catch the early-morning sun overlooking what might once have been a tiny corner of England, transplanted by the cubic foot of earth into the red-clay dirt of the Sierra Foothills.

That same dirt was now the dust that stained the windows, layering every nuance of the old room in hints of bloody deeds.

The tattered curtains no longer blocked out the harsh sun of morning, and the wallpaper curled from the walls in crackled strips. The carpet threads lay bare to the hard soles of the doctor who tended to the dying old woman, but she had no eyes for the living person taking her pulse, giving her surcease from pain, making her last hours bearable.

Her eyes were all for Angel—but nobody else could see him, so he rather regretfully assumed that she appeared crazy to the other people in the room.

“No,” she snapped contentiously. “I won’t tell you. I won’t. It’s not fair.”

Angel gave a frustrated groan and ran fingers through imaginary hair. This was getting tiresome.

“Old woman—”

“Ruth,” she snarled. “You used me up, sucked away my youth, drained me fucking dry. At least get my name right!”

Angel winced. The old wom—Ruth—had a point.

“I’m sorry the task was so difficult,” Angel said gently, containing supreme frustration. She was right. What Angel had asked Ruth Henderson to do with her life had been horrible. Painful. An assault on her senses every day she lived. But Angel needed the name of her successor—he needed to find the person and introduce himself. Angel really couldn’t leave Daisy Place unless he was in company of someone connected to it by blood or spirit.

“You are not sorry,” Ruth sneered. “You could give a shit.” She looked so sweet—like Granny from a Sylvester the Cat cartoon, complete with snowy white braids pinned up to circle her head. She’d asked her nurse to do that for her yesterday, and Angel, as sad and desperate as the situation was, had backed off while the nurse worked and Ruth hummed an Elvis Presley song under her breath. The music had been popular when Ruth was a teenager, and it was almost a smack in Angel’s face.

Yes, Angel had taken up most of her life with a quest nobody else could understand, and now Ruth’s life was ending and Angel was taking the peace that should have held sway.

Her breath was congested and her voice clogged. Her heart was stuttering, and her lungs were filling with fluid, her body failing with every curse she lifted. She’d been a good woman, performing her duty without question at the expense of family, lovers, children of her own.

It was a shock, really, how bitter she’d become as the end neared. A pang of remorse pierced Angel’s heart; the poor woman had been driven beyond endurance, and it was Angel’s fault. It was just that there were so many here, so many voices, and Angel would never be released, would be trapped here in this portal of souls until the very last one was freed. Angel was incorporeal. Ruth was the human needed to give voice to the souls trapped in this house, on these grounds. If she didn’t give a very human catharsis to the dead, they would never rise beyond the soul trap this place had become.

And now that she was dying, she needed to name a successor, or everybody trapped at Daisy Place would be doomed—Angel included.

“I’m sorry,” Angel said, regret weighting every word. “It probably seems as though I didn’t care—I handled everything all wrong. We could have been friends. I could have been your companion and not your tormenter. You deserved a friend, Ruth. I was not that friend. I’m so sorry.”

Ruth blew out a breath. Her words were mumbles now—Angel understood, even if the doctor and nurse at her bedside assumed she was out of her mind.

“You weren’t so bad,” she wheezed. “You were in pain.” A slight smile flickered over the canvas of wrinkles that made up her face. “You made my garden bloom. You couldn’t prune for shit, but you did try.”

“It gave me great joy,” Angel confessed humbly. No more than the truth. Angel had loved that garden, loved the optimism that had laid the fine Kentucky bluegrass sod and ordered the specialty rose grafts from Portland and Vancouver. No, Angel couldn’t prune it—couldn’t hold the shears, couldn’t hold back the tide of entropy that the garden had become—but that hadn’t stopped the place from being Angel’s greatest source of peace, even stuck here in this way station for the damned and the enlightened.

“I know it did.” There was defeat in Ruth’s voice. “Promise me,” she mumbled.

“What?” Angel would take care of the garden until freed from this prison—there was no question.

“Promise me you’ll be kind to him.”

Oh! Oh sweet divinity. She was going to name an heir.

“To him?” Angel asked, all respect.

“I left him the house, but the boy hasn’t had it easy, Angel. He’ll be here soon enough. Be kind.”

“I need his name,” Angel confessed. “If I don’t know his name, I’ll never find his soul.”

“Tucke

r,” she whispered, her last breaths rattling in her chest. “My brother’s boy. Tucker Henderson. Be kind,” she begged. “He’s a sweet boy…. Be kind.”

Triumph soared in Angel’s chest. Yes! Ruth Henderson’s successor, the empath who could hear the ghosts and help exorcise Daisy Place! Angel wanted to cheer, but now was not the time. With invisible hands but tenderness nonetheless, Ruth Henderson’s ghostly companion stroked her forehead and whispered truths about a glorious garden in the afterlife as the good woman breathed her last.

Blind Faith

TUCKER DIDN’T know how it happened—he never knew how it happened. One minute he’d be walking into a restaurant for dinner, and the next a stranger would stop by his table and strike up a conversation. Twelve hours later, Tucker would have a new friend—and a few used condoms.

It had cost him girlfriends—and boyfriends. He never planned to be unfaithful. He rarely planned to go into the restaurant or bar at all. He’d be strolling down the street, a bag of groceries in his hand and a plan for dinner with—once upon a time—friends, and he’d feel a draw, an irresistible pull, a rope under his breastbone tugging him painfully into another person’s bed.

He’d tried to resist on occasion, back when he’d had plans for a normal life.

When he’d been younger—a green kid freshly grieving the loss of his parents—it had worked out okay of course. Any touch had been okay. He’d been alone in the world, and the empathic powers his aunt Ruth had warned him about had arrived, and suddenly he was seeing a host of people who shouldn’t exist, wandering around in the world like everyday folk.

Sex had been comforting then.

He’d lost his virginity when he’d gone into a McDonald’s for a soda after school and ended up trading blowjobs with the cashier—who happened to be his high school’s quarterback—in the bathroom.

They had both been surprised (to say the least), but then Trace Appleby had broken down into tears and wept on Tucker’s shoulder because he’d never been able to admit he was gay until just that moment. He said he’d been thinking about taking drastic measures, and although he’d never been more explicit than that, Tucker had gotten his first inkling of what was to come.

Given how lost he’d been, how heartsore, it had seemed like a karmic mission of sorts. He was kind of excited to see what came next.

Next had been right after high school graduation, when he’d been working at McDonald’s—he and a friend had ended up doing it in her car in the upper parking lot. Afterward, she had broken down on a bemused Tucker and told him that her boyfriend had been cheating on her but she didn’t have the courage to leave him.

Until right then.

Tucker started to harbor suspicions that next might not be as wonderful as he’d hoped.

Less than a month later, when he stood up a girl he liked because he’d wandered into a bar and slept with a guy who’d been thinking about going to a party so he could get high and woke up thinking about college instead, Tucker began to understand.

And the only comfort sex had offered him then had been the comfort he apparently gave others in bed.

He’d explained it to his friend Damien the next day. First, Damien had needed to get over the “Oh my God, you’re bi?” But after that he’d been pretty copacetic.

“So you’re saying God wants you to get laid,” he’d concluded.

Tucker sort of frowned. “That does not sound like the Sunday school lessons I got growing up,” he said. Of course, his parents had been gone for about two years at this point, and he hadn’t attended a church service in a very long time.

Then he remembered something his father had said.

He’d been born late in his parents’ life—they’d been in their fifties when their car had skidded off the road during their date night—but his father had been a kind man, active, with salt-and-pepper hair that hadn’t even started to thin. He’d had laugh lines and kind brown eyes, and he’d told Tucker to go to church and soak up the feeling—the feeling of being protected.

“Ignore the words, son. Some people need them, but you’re just there to know what it’s like to find shelter from the storm.”

Oh. Apparently Tucker was shelter from the storm. Maybe God really did want him to get laid. Or the gods, really. Tucker had already identified vampires and elves and ghosts and werecreatures among the hosts of not-humans who walked the city streets with him. In an effort to broaden his knowledge, he’d begun taking classes in comparative religion, ancient language, arcane lore, and anything he could find even remotely connected. School was fun at that point—but the broader lessons hadn’t started to set in.

He looked at Damien, wishing that Damie was bi too, because he had a rich red mouth and dark blond hair and green eyes and freckled cheeks, and Tucker had wanted to kiss him for a long time.

But Damien was the kind of guy who always landed on his feet. If he got detention in school, he’d meet a pretty girl who’d want to be taken out Saturday night. Once when he’d been out of work, his car had broken down, and the Starbucks he’d gone into while he waited for the tow truck had been looking for a cashier.

Damien always found a sheltered path through life’s difficulties, simply on instinct. He never needed shelter from the storm.

He’d never need Tucker.

Tucker had always been the guy with pencils when the teacher gave a surprise test, the guy with the extra sandwich when someone forgot their lunch, or the guy with the spare jacket or the shoulder to cry on. Even before the McDonald’s blowjob and the sobbing quarterback, Tucker had a reputation as the guy people could talk to when life threw them a curve ball. He was a sympathetic ear.

Or an empathetic ear.

Talking to Damien, remembering his father’s definition of religion in contrast to his college professors’, it occurred to him that being the sympathetic ear might have become his cosmic mission in life—with the added twist of sex. Suddenly both the sympathy and the sex felt like a chore.

“Never mind,” Tucker had said, his heart breaking for the things he was starting to see he’d never have. “I get it now. I’m an umbrella.”

“And I’m an ice cream cone,” Damien replied, because he thought that was the game.

Tucker hadn’t been able to play, though. He was too busy thinking about how many ways being an umbrella could go wrong.

He’d found them. One night when he was in his twenties, he’d resisted the pull, sobbing from the wrongness in his chest, the displaced time, the pull in his blood and corpuscles to wander into a restaurant and come home with God or Goddess knows who. But he wanted to be faithful—his heart was faithful, dammit, why couldn’t his body be?

He’d gotten home to a message on his phone—the father of the girl he’d fallen in love with had died, and she’d needed to leave town.

Tucker could have written it down to coincidence, but by then he didn’t believe in coincidence. He’d given up on relationships for a while.

Not long enough, but a while.

And that had been many years and one eon of heartbreak ago.

So by the time he arrived at Daisy Place, he was tired, old at thirty-five, exhausted by his karmic mission, and so, so lonely.

But by then his gift, the empathic pull that led him to other people’s beds and their cosmic epiphanies and karmic catharses, had been honed to a science. It had used him often enough that he knew what to expect.

The night the Greyhound dropped him off in the middle of what kind of passed for a town, suitcases in hand like a kid in an old musical, he didn’t set about trying to find a ride to Daisy Place immediately. Sure, the press under his breastbone had started almost directly after he’d gotten the call from his aunt Ruth’s lawyer, and it had been subtly building ever since, but he knew this game well enough to know that Daisy Place wasn’t at critical mass yet. First, he needed a room to sleep in—and he’d felt the other pull, the older, more painful pull, for a mile before the bus had slowed at the depot.

So

meone here would give him a place to sleep, and he could see to Aunt Ruth’s inheritance in the cold light of day.

Sure enough, he was in the middle of a ginormous hamburger that had been cooked in an actual ore cart from the gold-rush days, when a tired-looking woman in nice comfy jeans, a skinny-strapped tank top, and flip-flops strode into the converted post office/restaurant and threw herself into a chair at the table next to him.

The restless, painful ache in his chest that had guided him there gave a little pop, and he could breathe again.

“Hey there, pretty lady,” he said, shoving a plate of fries toward her. “Is there anything I can do to help?”

She had blond hair—artfully streaked and ironed straight—adorable chipmunk cheeks, and a full and smiling mouth. The girl took a fry gratefully and tried to put that mouth to happy use. She failed dismally, but Tucker appreciated the attempt. Putting a good face on things for other people was an unnecessary courtesy, but it was still kind. Thin as a rail, with a few subtle curves, she was in her late twenties at the most and seemed to have the weight of the world on her shoulders.

“It’s been sort of a day,” she said fretfully. “You know—a day?”

Tucker thought back to when he and Damien used to have this discussion, and his stomach twisted hard with regret. “I’ve had a few,” he said softly. “What happened with yours?”

“It’s just so stupid.” She sighed and looked yearningly at the untouched half of his two-pound hamburger. Tucker cut off a quarter of it and put it on the fry plate for her, and her smile grew misty.

“Thank you,” she said softly. “I mean, I was going to order my own, but eating alone….”

“Sucks,” he said, nodding. “So, I’m Tucker Henderson—”

“Old Ruth’s nephew?” she said with interest.

“Yes, ma’am.” He hadn’t seen Aunt Ruth in several years. She’d helped administer his parents’ estate, sending him personal checks every month—ostensibly to help him through college, but the estate was more than enough to live on. He’d appreciated the gesture, though, and had called or written with every check, but she’d never asked him up to see her at Daisy Place, and Tucker….

Super Sock Man

Super Sock Man Safe Heart (Dreamspun Desires Book 102)

Safe Heart (Dreamspun Desires Book 102) Slow Pitch

Slow Pitch School of Fish

School of Fish Shades of Henry (The Flophouse Book 1)

Shades of Henry (The Flophouse Book 1) Ethan in Gold

Ethan in Gold Hidden Heart

Hidden Heart Familiar Demon

Familiar Demon Shortbread and Shadows

Shortbread and Shadows Silent Heart

Silent Heart Shortbread and Shadows (Dreamspun Beyond Book 41)

Shortbread and Shadows (Dreamspun Beyond Book 41) All the Rules of Heaven

All the Rules of Heaven Shades of Henry

Shades of Henry Homebird

Homebird Under the Rushes

Under the Rushes Fish on a Bicycle

Fish on a Bicycle Warm Heart

Warm Heart The Muscle

The Muscle The Bells of Times Square

The Bells of Times Square![Jack&Teague [& Katy] stories 1-5 Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/19/jackandteague_and_katy_stories_1-5_preview.jpg) Jack&Teague [& Katy] stories 1-5

Jack&Teague [& Katy] stories 1-5 Wounded, Volume 1

Wounded, Volume 1 Paint It Black

Paint It Black The Virgin Manny

The Virgin Manny Fall through Spring

Fall through Spring Clear Water

Clear Water If I Must Lane

If I Must Lane Stand by Your Manny

Stand by Your Manny Hiding the Moon

Hiding the Moon Freckles

Freckles Chase in Shadow

Chase in Shadow Sidecar

Sidecar Quickening, Volume 1

Quickening, Volume 1 Black John

Black John Bobby Green

Bobby Green Winter Ball

Winter Ball Hammer & Air

Hammer & Air A Few Good Fish

A Few Good Fish Dex in Blue

Dex in Blue Quickening, Volume 2

Quickening, Volume 2 A Fool and His Manny

A Fool and His Manny Manny Get Your Guy (Dreamspun Desires Book 37)

Manny Get Your Guy (Dreamspun Desires Book 37) Familiar Angel

Familiar Angel Bonfires

Bonfires The Locker Room

The Locker Room Rampant, Volume 2

Rampant, Volume 2 Left on St. Truth-Be-Well

Left on St. Truth-Be-Well A Solid Core of Alpha

A Solid Core of Alpha Red Fish, Dead Fish

Red Fish, Dead Fish Summer Lessons

Summer Lessons Country Mouse

Country Mouse City Mouse

City Mouse Turkey in the Snow

Turkey in the Snow Rampant, Volume 1

Rampant, Volume 1 Bitter Moon Saga

Bitter Moon Saga Candy Man

Candy Man Crocus

Crocus Green's Hill Werewolves, Volume 2

Green's Hill Werewolves, Volume 2 The Green's Hill Novellas

The Green's Hill Novellas