Clear Water Read online

Copyright

Published by

Dreamspinner Press

382 NE 191st Street #88329

Miami, FL 33179-3899, USA

http://www.dreamspinnerpress.com/

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

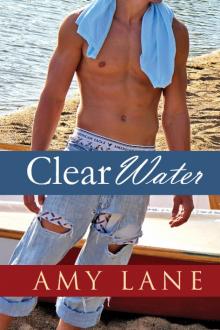

Clear Water

Copyright © 2011 by Amy Lane

Cover Art by Dan Skinner/Cerberus Inc. [email protected]

Cover Design by Anne Cain

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system without the written permission of the Publisher, except where permitted by law. To request permission and all other inquiries, contact Dreamspinner Press, 382 NE 191st Street #88329, Miami, FL 33179-3899, USA

http://www.dreamspinnerpress.com/

ISBN: 978-1-61372-191-9

Printed in the United States of America

First Edition

September 2011

eBook edition available

eBook ISBN: 978-1-61372-192-6

Dedication

To My Odd Little Duck

Author’s Note

SO THERE I was, sitting with my husband in a class for parents with children with ADHD. I had my knitting with me—because I can never sit still without it—and I was checking out the other people with their knitting and then starting to put together backstories on the people who were sitting in the room. Were they grandparents? Parents? Aunts? Uncles? Were their children seven, like ours? Teenagers? Was this for themselves?

I was well on my way on both the sock I was working on and several promising stories in my head when the instructor said, “Attention deficit problems are usually passed down through the genes. So if you are here for someone in your family, odds are, an adult you know deals with these problems all the time.”

The irony was not lost on me. I tugged my husband’s sleeve (because he doesn’t have trouble paying attention at lectures) and said, “So, hon, which one of us do you think our odd little duck got this from?”

My husband looked at me with patient eyes. “Your father,” he said with a perfectly straight face.

God, I love that man.

So in addition to learning that about ourselves, I also learned that ADHD is usually not as much of a problem for adults as it is for kids. Once an adult can control his/her environment, he/she tends to avoid situations in which that frog-jumping attention gets them into trouble. But not all adults. Some adults still need the medication, and some of them still need a little bit of prompting, and of course, all of us need reminding that the things that make us different may be anomalies, but they are not abnormal.

And that’s where the idea for Patrick was born. Here’s hoping my own odd little duck has as much luck in finding a mate as his mother—or the odd little frog in his mother’s book.

Amy

Trix

One Sip

“DAD, I’m gay.”

Patrick Cleary stood at the breakfast table of their obscenely large home in the rich people’s suburb in Orangevale and ripped one thumbnail off with another. It was six in the morning at the end of May, which meant the light was strong enough for his father to squint at him when he looked up from his Cheerios with Splenda and the laptop with the morning financial report.

“Since when?”

Shawn Cleary was not originally a businessman. Originally, he’d been a trade worker in a computer factory in West Sacramento. Before Patrick had been born, Hewlett-Packard and Intel had pulled away all of the small firm’s business, but Shawn Cleary—smarter than the average bear, as he liked to say—had taken out a loan to recycle the old computers as opposed to making new ones, and it had made him rich. Dirty, rotten, filthy, stinking rich.

Or at least that was what Shawn liked to say.

Patrick liked the money. He didn’t see anything dirty, rotten, filthy, or stinking about it. The money had kept him in trendy clothes and first-rate sunglasses all through high school and up to his ass in ass afterward. But it was one thing to tell your dad you were going out to a friend’s when you were really going out to a boyfriend’s to get laid, and it was another to look at him, day after day, when you were fiddle-fucking around with your life and confess to the reason why.

Fact was, he didn’t feel like starting a real life unless he could start a real life, like maybe the type of real life where he could tell Dad that he was going to his boyfriend’s house, and maybe invite Cal over to dinner, and basically be kind of a family, since Mom had left with her personal trainer and it had just been the two of them for so long. So he was ready. He was ready to go back to college and get a degree in science, and ready to stop fiddle-fucking around at parties, and ready to be a stand-up guy and be up front with his old man.

But first he had to look him in the eye and tell him the gawdshonesttruth.

“Since forever,” he rasped, looking at Shawn anxiously.

Shawn’s ginger hair had gotten grizzled as he’d aged, and although his freckled skin was almost perpetually light tan, the freckles were still there, along with the bright blue eyes. The lines around his eyes and mouth had deepened in the last eight years since Mom had left, but mostly, he was still vital, strong, and terrifying. Oh, sure, Shawn loved him—Patrick hoped he did, anyway. But he’d always been a member of the “To love me is to fear me a little” school of parenting, and Patrick had been a very good student.

“Bullshit,” Shawn snorted, and went back to his laptop.

Patrick blinked. Bullshit? Bullshit?! Bullshit?

“Bullshit?”

“Yeah, bullshit. You’re no more gay than you were an artist, or a scientist, or a firefighter, or whatever the hell you wanted to be last week—”

“A yoga instructor.” The health club had actually offered him a job. He’d been excited about it, too, right up until Shawn had snorted in his face and said, “Yeah, right!”

“Yeah, well, you weren’t serious about that, were you?”

“I thought it would pay for my books when I went back to school,” Patrick said numbly. He had—it had been his plan, and it had looked glorious in his head, right up until that snorted “yeah, right!” Little did he know, Patrick thought. He’d had no idea, none at all, that “yeah, right!” was apparently one or two steps above “Bullshit!” on the parental fuck-you-o-meter.

“What the hell are you going back to school for?” Shawn snorted, and Patrick flushed.

“A degree in science,” he said softly, “and a law degree after that.”

Shawn put down his spoon. “What in the hell would you want a law degree for?”

“To be an environmental defense lawyer—you know, save the planet, like you?” Patrick hated himself for that last part—true or not, he hated himself for it.

Shawn’s jaw tightened like he was touched—or had indigestion—and he grunted and looked down at his cereal. “Not trying to change the world, dumbass. Just trying to make a buck.”

Patrick mashed his teeth together so hard it hurt. “Look, Dad—I’m not saying this to piss you off or whatever. I’ve just… you keep giving me shit about being a virgin because I haven’t had any girlfriends. It’s just that I’m not a virgin, but I still haven’t had any girlfriends!”

Shawn Cleary spit out his Cheerios and Splenda. “What in the fuck?” He glowered up at his son, and Patrick stood his ground.

“Please tell me this doesn’t change the way you feel about me?”

It was the question

at the end that did it, Patrick decided later, after way too much self-pity and the roofie Cal had slipped him because it turned out he wasn’t Patrick’s dream boy after all, just some cocksucker out for easy money and a piece of ass. It had been the question at the end. Shawn Cleary appreciated people who knew their own mind. Owning up to something, sticking by your guns. That pathetic baby whimper at the end of the sentence was really what spun Shawn’s wheels, not the gay. At least that was what Patrick told people after Shawn stood up and started shouting.

“Feel about you? You want to know what I feel about you? I’ll tell you what I feel about you! You’re a fuckup, Patrick! Your biggest accomplishment is graduating high school and leeching off my money! What in the hell do you want me to say? ‘You’re gay! Hur-fucking-ray!’ Go ahead—fuck every guy that moves! I don’t give a shit—just don’t expect me to gravy-train your little homo-express because you can’t decide what else to do with your life, okay?”

Patrick had spent a lot of time in his life pretending it was all okay. The day after his mom had run away, he came downstairs to find Shawn at the breakfast table, eating Cheerios and sugar, and looking at the financial report. Patrick had sat across from his father, fixed himself some toast and some orange juice, and then left for school.

“Bye, Dad.”

“Have a good day.”

Patrick always figured it was a good thing his mom left after he got his driver’s license, because if he’d had to interrupt Patrick’s work schedule, then they might have had to talk.

As he stood now and fought his quivering chin, he realized that maybe talking was overrated. Maybe talking sowed the seeds of destruction. Maybe talking was… oh, hell. He had to get the fuck out of there.

“I’m sorry I’m a disappointment,” he said quietly, and then turned around and left.

He didn’t stop to see the look on his father’s face, and he was glad, because his worst fear was maybe Shawn Cleary wouldn’t be sorry, not even a little bit sorry at all.

CAL had a job—not that Patrick knew what he did—but he got off at six and met Patrick at their favorite bar, the one down off of Del Paso Heights in Sacramento where men were allowed to dance with men. Patrick had gone back to the house after his father left, and packed an overnight bag and met Cal with a hope to stay in Cal’s little one-bedroom apartment until he could see if that yoga instructor’s position was still waiting for him, or maybe he could wait tables. It would be okay—they didn’t need Shawn Cleary’s money, right? They had each other, right? And Patrick’s plan hadn’t changed. Kids put themselves through school all the time. Patrick had gotten good grades—he had sixty units from community college; he wasn’t a complete fuck up, right? They could do this. They were in love.

Cal had a thin face with dark hair and a widow’s peak that was starting to pronounce, even at twenty-five. His best assets were his stunning blue eyes with their thick dark lashes, and Patrick had always seen them laughing or planning or bright with sex and passion.

He didn’t know then that contempt would make them narrow at the corners and bring out the bags under them or the sallowness that came from tweaking a little too often. He didn’t realize that Cal’s disgust would practically have color, taste and smell. He only knew that he felt those blows through his body like whiplash, and he felt like one big limpid puddle of hurt.

“Cal?”

Cal shook his head and for a minute, that horrible look of revulsion faded away. “Yeah. Look. I’m sorry. I… you really think we’re going to live without your dad’s money? You didn’t say anything unforgivable, did you?”

Patrick fought the urge to sniffle like a toddler. “He didn’t even say I was cut off. I just don’t want to live with him if he’s not going to take me seriously!”

Cal snorted. “Well Jesus, Patrick! It’s not like you’re built for the real world or anything, you know? You don’t have a job skill—hell, I don’t even think you’ve ever worked a real job!”

Patrick cringed. “I have too,” he said, unhappy that Cal would forget this. “I waited tables for a year and a half in that restaurant across town!” He’d loved that job, actually. He’d worked hard, no one had treated him special, and he’d been, once again, up to his ass in ass. (Or rather, Ricky the cook had been up to his balls in Patrick’s ass. Patrick had quit the job when he found out that Ricky had been taking it bareback in the walk-in from Eduardo, the head bartender, the whole time, which was so not cool and made Patrick three times as cautious about always using a condom and twice as cautious about finding a boyfriend after that.)

“Oh yeah,” Cal said, and Patrick had to look hard at him to make sure he wasn’t rolling his eyes. “Wasn’t that just before we met?”

Patrick nodded, and Cal chewed his lower lip.

“So, uhm, this desire for independence has been building for a while, hasn’t it?”

“Yeah,” Patrick said softly, thinking about all that excitement he’d had for going back to school. “I was good in school, when I took my meds—I’d like to go back, study something I’m interested in, you know?”

“But… I don’t know, Patrick—don’t you have everything you want right now? I mean, living on your Dad’s dime, nothing wrong with that, right?” Patrick was going to protest, but then Cal did that thing he did where he put his hand on the side of Patrick’s face and kissed him on the forehead and made him feel like a little kid, protected and cherished and small. “Besides, baby—who needs those nasty old meds polluting your system, right?”

Patrick smiled thinly. He’d never been able to get Cal to understand the Ritalin or how badly he seemed to need it sometimes. His dad hadn’t gotten it either, and his mom—well, his mom made sure he always had it, and then burst into tears when it wore off. People assumed that the drugs were a crutch, something that made keeping his brain on the right track easy, and that he was just lazy because he couldn’t focus. They didn’t understand that with the drugs, making little choices—listen or fidget, hear instructions or think about what he had for breakfast—became possible. He could see the little choices with the drugs—they were laid out for him as neatly as clothes folded on the bed, and all he had to do was take a breath and make a choice.

Without the drugs, his brain was one big hairy garage sale in the jungle, and he had no idea where to find anything, and sometimes, the sheer frustration just took over and made him a tense, whiny, squalling infant, even at the age of almost twenty-four.

When Cal patted his cheek like that, he did feel comforted and cherished and cared for, and he needed that, because he was totally incapable of navigating the uncharted garage sale of his own mind.

But he’d had his meds today. He’d been taking them for the past two months—they’d helped him negotiate the paperwork jungle of re-enrolling in school and deciding on a major and then even the complex reasoning behind his own delayed maturity. He’d been able to think, dammit, and he liked it. He just didn’t want to tell Cal, because then there’d be a big furry argument about it, and as much as he thought Cal loved him, he didn’t want to test that with the little prescription bottle in his pocket.

“I just want to be able to make my own way,” he mumbled now. “My father did it, right?”

“Yeah, baby—here, have a beer.” Cal gave the universal gesture for “draft,” and the bartender nodded his head, raising his eyebrow at Patrick, who’d been drinking soda for the past hour as he’d waited for Cal to get off work.

Beer wasn’t good—not with his meds—but he didn’t want to fight with Cal. He figured he’d nurse it—just take a couple of sips and leave the rest while they tried to hash out their future in the wake of the train wreck Patrick had just had with his father.

Cal smiled at him as the beers were served and rubbed their noses together. “It’s okay, Trix,” he promised gently. “I’m gonna make you feel alright.”

One drink of beer. He swore that was all he had.

Whiskey

A Regrettable Deed

WESLEY KEENAN couldn’t sleep, which really pissed him off. The little houseboat in the delta had proved to be the one place he could sleep, ever, and that was a surprise, since most of it was a science lab and the bed in the back was a tad on the small side. But on this hot late May night, he couldn’t sleep, which was how he came to be out walking in the bogs and the marshes between the marina and the levee.

He sort of liked it out here.

Of course, he’d originally only ended up here because that was where the research had taken him. He’d seen the data, written the grant, rented the houseboat, and determined to live with the bog smell and the mild traffic noises and the diesel that the other houseboats kicked up because apparently he was the only one capable of converting a diesel engine to one that ran cleanly on biofuel. But eventually even the humidity of the delta and the weird mix of political town and cow town mentalities started to fade. On nights like this, he would listen to the traffic from the levee and the sound of the river lapping on the sides of the houseboats, then look into the sky, which was surprisingly free of light pollution this far from the city proper, and he’d think that maybe, when the grant ran out, he’d keep the houseboat and write his next grant from here.

It wasn’t an entirely awful idea, and that surprised the hell out of him too.

So he was picking his way among the grass hummocks, trying not to sink too far into the mud as the bog narrowed to the place where the river ran right alongside the levee, when he heard the nasty metal-bending sound of a car going through a guard rail.

He looked up just in time to see the bright yellow Honda Jazz cut a lovely arc through the air and do the plunge-n-bounce into the deep waters of the river.

He had that moment of shock that most people would have, that “Oh-my-God-I-can’t-believe-that-just-happened!” moment, and he saw two things.

Super Sock Man

Super Sock Man Safe Heart (Dreamspun Desires Book 102)

Safe Heart (Dreamspun Desires Book 102) Slow Pitch

Slow Pitch School of Fish

School of Fish Shades of Henry (The Flophouse Book 1)

Shades of Henry (The Flophouse Book 1) Ethan in Gold

Ethan in Gold Hidden Heart

Hidden Heart Familiar Demon

Familiar Demon Shortbread and Shadows

Shortbread and Shadows Silent Heart

Silent Heart Shortbread and Shadows (Dreamspun Beyond Book 41)

Shortbread and Shadows (Dreamspun Beyond Book 41) All the Rules of Heaven

All the Rules of Heaven Shades of Henry

Shades of Henry Homebird

Homebird Under the Rushes

Under the Rushes Fish on a Bicycle

Fish on a Bicycle Warm Heart

Warm Heart The Muscle

The Muscle The Bells of Times Square

The Bells of Times Square![Jack&Teague [& Katy] stories 1-5 Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/19/jackandteague_and_katy_stories_1-5_preview.jpg) Jack&Teague [& Katy] stories 1-5

Jack&Teague [& Katy] stories 1-5 Wounded, Volume 1

Wounded, Volume 1 Paint It Black

Paint It Black The Virgin Manny

The Virgin Manny Fall through Spring

Fall through Spring Clear Water

Clear Water If I Must Lane

If I Must Lane Stand by Your Manny

Stand by Your Manny Hiding the Moon

Hiding the Moon Freckles

Freckles Chase in Shadow

Chase in Shadow Sidecar

Sidecar Quickening, Volume 1

Quickening, Volume 1 Black John

Black John Bobby Green

Bobby Green Winter Ball

Winter Ball Hammer & Air

Hammer & Air A Few Good Fish

A Few Good Fish Dex in Blue

Dex in Blue Quickening, Volume 2

Quickening, Volume 2 A Fool and His Manny

A Fool and His Manny Manny Get Your Guy (Dreamspun Desires Book 37)

Manny Get Your Guy (Dreamspun Desires Book 37) Familiar Angel

Familiar Angel Bonfires

Bonfires The Locker Room

The Locker Room Rampant, Volume 2

Rampant, Volume 2 Left on St. Truth-Be-Well

Left on St. Truth-Be-Well A Solid Core of Alpha

A Solid Core of Alpha Red Fish, Dead Fish

Red Fish, Dead Fish Summer Lessons

Summer Lessons Country Mouse

Country Mouse City Mouse

City Mouse Turkey in the Snow

Turkey in the Snow Rampant, Volume 1

Rampant, Volume 1 Bitter Moon Saga

Bitter Moon Saga Candy Man

Candy Man Crocus

Crocus Green's Hill Werewolves, Volume 2

Green's Hill Werewolves, Volume 2 The Green's Hill Novellas

The Green's Hill Novellas