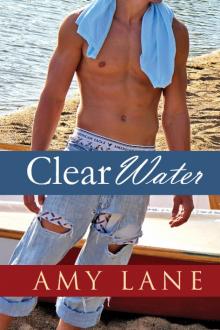

Clear Water Read online

Page 2

One was that the driver’s side window had been rolled down and there was someone escaping through the driver’s side, and he was greatly relieved. The other was that the person in the passenger’s seat wasn’t moving at all, and Whiskey was suddenly panicked. The water here was deep, and there was a current, and if someone was going to rescue that still form in the passenger side, it had to be done now!

Whiskey wasn’t even aware he was moving until he was halfway out to the steadily sinking car.

The water was cold enough to shock but not dangerous, and that was a blessing, but Whiskey’s heart was thundering in his ears, and he couldn’t say that was quite a good thing. He kept trying to remember how deep the water was here and when the car would level out, but he thought it was nearly fifteen feet, and it was night, so seeing in it was not going to be so easy.

And the car was filling up from the driver’s side—he could see that now—and it was starting to tip sideways and trap air in the passenger’s side. Fuck.

Whiskey worked out like a madman to keep his over-thirty-five love handles at bay, and he was damned grateful when he managed to wriggle in that window along with all of the water. When he got there, he flailed for a minute before he remembered that episode of Mythbusters that said the electronic windows would work even when wet.

He reached over the passenger—a young man who was still breathing out but not quickly—and rolled down the window, feeling some relief as the car leveled a little in its descent to the bottom of the river.

It was the eeriest thirty seconds of Whiskey’s life. He kept his face above water (and propped anonymous kid’s face up with his) until it was no longer possible and then went to work on the seat belt. Great. Floppy kid in his arms, seatbelt undone, no air… no air… no air… blurg-thump. The car made a sound as it hit, front wheels first, then back, and then Whiskey had endured about enough of that crap and opened the door.

Oh God bless Mythbusters and Adam and Jamie and their whole goddamned crew, because the door opened and he could drag anonymous teenager to the surface.

He got there, dragging air into his lungs with more appreciation of oxygen than he’d ever had before, his arm around his crash victim’s chest, keeping the kid up, and… was he breathing? Aw, fuck. Whiskey couldn’t be sure, but he couldn’t give him mouth to mouth in the river either.

Still gasping, he kept swimming, strong and steady, until his long legs found the silt under his feet and he started hauling himself and the boy’s body through the weeds and the muck at the riverbank. His battered tennis shoes squelched uncomfortably with every step, and the stench of the decaying marsh plants and diesel oil was almost overwhelming here. The next day, he’d be grateful they hadn’t surfaced at one of the parts of the river with the ankle-breaking rocks—but that would be the next day.

He had the kid under the arms, and when he got to a flat spot, he dropped him perfunctorily and got on his knees, prepared to do the mouth-to-mouth thing before calling for help. (Somewhere out there was a proscription against starting mouth-to-mouth without witnesses, but Whiskey had never been great at rules anyway.)

He didn’t need to—the boy’s body collapsed down enough to force a little water from his lungs. He started coughing, still unconscious, and Whiskey turned him over on his side, where he proceeded barf nasty water for a few minutes before settling down a little.

Not once did he wake up or even open his eyes.

Whiskey looked at the boy helplessly and then looked out to the river to where the car was probably being dragged by the current to parts unknown. He knew that somewhere downstream, where the river opened up into the Delta, there were breakwaters and places where bodies and junk and sunken motorboats washed ashore, but he was pretty sure the car was a write-off, no matter what. He looked around, expecting to hear sirens at any second, and realized that the boy’s companion, the driver of the damned car, had taken off.

Whiskey frisked the kid and came up with a small prescription bottle for—squint at it in the light—“Patrick. Patrick Cleary.” Whiskey blinked. Well. Wasn’t that name familiar. “So, Patrick Cleary, what are we taking?” He read the label. “Concerta. What in the holy hells is ‘Concerta’, and why would it put you in a coma? Should be called ‘Comerta’, oh yes it should!” Whiskey’s sense of humor was not always appropriate, he was aware, but since the only person there to hear him was asleep, he decided he didn’t give a fuck and laughed at his own joke.

“Okay, Patrick Cleary, who was your skeezy friend, why did he run, and what in the fuck are we going to do about your car? These are things I’d very much like to know.”

At that point the boy did maybe his first almost-conscious thing since the car had plunged into the Sacramento River—he pulled his knees to his chest and started to cry, soundlessly, like he was dreaming about something sad. Whiskey looked at him in the thin light of the moon and the dissipated sodium glow from up on the levee and sighed. What looked to be dark-blond hair was plastered to his head—either salon-streaked or naturally, it was hard to tell—but his khakis and summer-weight blazer were fashionable and expensive. The kid had a small face, piquant, and almost round, although he actually looked a little thin under his blazer. Whiskey couldn’t tell if he was awake or simply crying in his sleep, but either way—God, what a forlorn little kitten he was, wasn’t he?

Whiskey sighed and crouched down, sliding his hands under the kid’s knees and his shoulder. Now that he was done barfing, it was time to get him somewhere he didn’t look so damned sad.

With a heave, a grunt, and a muttered curse word, Whiskey pushed himself up, a gangly bundle of teenager in his arms, and resolved himself to hauling the kid’s scrawny ass to the houseboat. His wet, holey jeans made schwacking sounds against themselves as he walked, and his T-shirt dripped mud and silt down to keep his jeans wet, in case they had random drying thoughts during the trip.

Fly Bait would hate this kid on sight.

“WHO in the holy fuck is that?”

Fly Bait didn’t often show emotion, which was why Whiskey no longer played poker with her. The houseboat had two berths, and she took one. Yeah, they’d knocked uglies before on another research excursion, but that had been out of sheer boredom. Whiskey tended to like his bed partners—female or male—to be a little more vocal. Fly Bait tended to like her bed partners a little more female, but, well, they’d been waiting for a species of fish to procreate when, in fact, the damned things had been all but sterile. Boredom? Whiskey swore his heart rate had been faster when he’d been sleeping than it had been on that job—or during the abortive sex with Fly Bait.

“An acolyte,” he muttered now, trying not to stagger down the stairs from the deck. Hell, he’d been half a mile away from the dock—who knew the little shit he was carrying weighed so much? The fun part had been walking on the unsteady quay on his unsteady legs—damn, he’d been half-afraid he’d pitch the poor kid off the edge and then follow him out of sheer embarrassment.

“Yeah?” Fly Bait had straight brown hair that fell right below her ears because she hacked it off herself that length whenever it threatened to overcome the ragged edges years of doing this had given her. She also had a thin oval of a face, flat brown eyes, and a sort of hidden patience. She could rip an unwary head and/or face off if she thought someone was skiving off or being deliberately stupid, but if she knew a member of a research team was honestly trying, she was perhaps one of the best field teachers Whiskey had ever met.

“Yup,” Whiskey muttered, staggering down the stairs to the hold, through the tiny living/dining room space that also converted into a bed, and into his berth, where he stripped the kid out of his stinking clothes down to his underwear. Then, balancing the kid against his shoulder, where he exhaled fetid breath with a soothing regularity, Whiskey threw an oversized towel over his coverlet and then another one over the kid. He hated going to the Laundromat, but he was damned if he would sleep in that reechy mess that the kid smelled like when helpless kitten here fin

ally went back to where he was supposed to go.

He emerged from the bedroom with a pair of boxer shorts, which was all he wore to bed and all Fly Bait cared that he wore, period, and promptly went to the head with its three-by-three shower cubicle of recycled water.

It was better than stinking up the boat even more than it already reeked, that was for certain.

He came out of the bathroom toweling his hair and sniffing experimentally at Fly Bait’s girl-floral shampoo, which still lingered in his hair. It was a hell of a lot better than river water and diesel oil, that was for damned sure.

“If he’s an acolyte,” Fly Bait said, looking up from her Scientific American as though their conversation had never been interrupted, “what’s he worship?”

Whiskey raised his eyebrows in thought. “Oxygen,” he said, nodding his head. “Since I bailed him out of the river, I think he’s a fan.”

Fly Bait blinked. For her, it was the equivalent of sitting up and shrieking, “Are you fucking shitting me?!” at the top of her lungs.

“Is this acolyte going to have any fellows?” she asked cautiously, obviously thinking hard.

Whiskey was way ahead of her. “I doubt it. The skeezemonkey who bailed out of the driver’s side isn’t coming back for him. Although….” Whiskey got a trash bag and stuck his hand into the bathroom for his wet clothes, then paused in front of his berth before getting Junior’s.

“Although?”

“Although it probably wasn’t skeezemonkey’s car.”

“What makes you say that?”

“’Cause it was sort of a sweet little ride, and skeezemonkey ditched it without a backward look. And… I’m probably thinking out of turn here….”

“Which would be different because?”

Whiskey shrugged. She had a point. The only time he wasn’t thinking out of turn was when he was applying for grants. “No reason. But I think he was drugged, and not in the fun way.”

Fly Bait’s eyes got really large at that. “So that would be the reason he hasn’t moved?”

“Yup. And it’s the reason I’m gonna stay up and shake him if he forgets to breathe, too. He threw up a lot of river water and probably anything else. If he wasn’t dead when the car hit the rail, I think he’ll be fine, but I want to make sure. Something about this whole thing….” Whiskey grunted. “Me no likey.”

He walked quietly into his tiny berth and pulled the wet clothes out of the plastic hamper, shoving them in the garbage bag. They were nice—slacks, summer weight blazer, a shirt that probably cost Whiskey’s clothing budget for the year if you counted underwear and socks. (Which were, actually, the things he wore the most.) Whiskey wondered about these clothes—they were a man’s size medium, but the belt was cinched up to an impossibly thin waist, and that boy… God, he’d looked fragile.

Whiskey walked the bag up to the deck, all the better to stink the next day when they visited the pier’s one washing machine, and returned down to the small living space, made even smaller by the equipment that he and Fly Bait were using this time out.

Fly Bait wasn’t even pretending to read her Scientific American anymore. He went to the small fridge and grabbed a soda and some salami and bread and plopped down on the couch to have himself a snack.

“He was pretty,” she said flatly, and Whiskey rolled his eyes.

“And very likely underage.”

“He’s in your bed.”

“Jealous?”

She blinked and canted her eyes to the side in a way that said she was honestly thinking about it. Then back. “No. Don’t think so. But we’ve got a very short time to do this—”

“I pulled him out of the river, Fly Bait—“

“Freya,” she corrected grimly, and she only did that when she was losing her patience with him.

“Freya,” he exaggerated. “Odds are good, when he wakes up, he’ll have something else to do. If nothing else, he’ll probably have a hangover that will rock a solid twelve on the Richter scale. So maybe stop prophesying doom for a second, and let me make sure he hasn’t choked on his own vomit before we kick him to the curb?”

“We could call the police,” she said pointedly, and he thought about it seriously.

“I don’t think so.”

“Any good reason why not?”

“He’s lost.” Whiskey shrugged. “I found him. If he wanders off, he wanders off, but in the meantime, we can afford to feed him.”

“That makes no sense at all,” she muttered.

He paused for a minute, trying to find words for the way that wordless, sobless crying had sunk into his soul and refused to budge. “He cried. He’s got a story. Cops come, no story. Maybe I’m interested.” Besides, both of them had perfectly good reasons for a lingering distrust of policemen to hang out in their psyches like the ghost of doobies past.

Fly Bait sniffed. “God, Whiskey, you are such a woman sometimes.”

Whiskey rolled his eyes. They both knew that if he were a woman, they would have been doing something entirely different when that car had gone through the rail.

THE bed in the berth was small, yes, but it could fit two, and eventually Whiskey pulled a blanket up over his shoulders and set his phone to wake him once an hour so he could check on Patrick’s breathing. Around four in the morning, the boy moaned and rolled over in his sleep, snuggling like an infant.

Whiskey sighed. “You know, kid, it’s a good thing I swing this way sometimes.”

It was wonderful, actually. The boy was trusting and soft. Whiskey didn’t trust it himself—he’d been jumping political hoops for far too long to have any faith in innocence. With a grunt, he pulled some of that crusty blond hair back from the delicate, small, round, pretty face and tried to analyze the kid’s motives even in his heavy, drug-induced sleep.

“Easy to trust, isn’t it, kid?” he muttered. “Easy to trust when you’ve got all that money to give you faith, huh?”

He said the words and then felt immediately guilty. The kid was as helpless as a tadpole in a shrinking pond. Whatever had happened to him, Whiskey thought it was more than apparent that he’d gotten here, in this tiny berth and in Whiskey’s bed, by trusting the wrong person.

The kid mumbled something in his sleep. It might have been anything, but Whiskey could have sworn he said, “Dad.”

Aw, fuck no! Not Daddy issues. Oh, Jesus. Kid—how did you end up here? But it didn’t matter, because as the kid snuggled in closer, Whiskey’s insomnia seemed to melt away. It was four in the morning, Whiskey had done his good deed for the decade, and Daddy issues or no Daddy issues, Whiskey was going to get some top quality, armful-of-twink sleep.

At 8 a.m. his alarm went off, and he wriggled out from between the kid and the wall muttering, “Fuck my life” repeatedly and trying very hard to ignore that the kid’s presence against the front of his body had made his morning wood difficult to deal with.

And then, to make matters worse, he got to the bottom of the bunk and threw on a clean (holey) T-shirt and a clean (holey) pair of jeans over his boxers, and looked up to find himself under the scrutiny of a shockingly blue (bloodshot) pair of eyes.

“You’re not Cal,” the kid said, the picture of befuddlement.

“Nope,” Whiskey said, finding his tennis shoes (holey) and putting them on without socks (because those were holey too, and that was where he drew the line.)

“Where’s Cal?” the kid asked plaintively. “And why do I smell like a sewer? And why does my mouth taste like ass?” Those blue eyes closed and the kid groaned. “Oh, Jesus, I’m sorry I’m sorry I’m sorry, why does my head feel like a fuckin’ bomb?”

That last came out as a whimper, and Whiskey watched as tears leaked out the corners of the kid’s eyes, making tracks down the grime left from his little foray into the river.

“Fuck my life,” he muttered, and then reached around in his drawer for a bottle of ibuprofen. “Be right back.”

The kid hadn’t moved when he came back with a big bottle o

f drinking water and broke the seal. “Here, kid. I’ll give you something for the pain, but you’ve got to drink this entire thing, okay?”

The kid whimpered, and Whiskey put strong, tanned fingers under the kid’s chin, even as he huddled under the covers, and forced the kid to look at him.

“If you want the pain to stop, sit up and do what I’m telling ya,” he growled, and the kid did, sitting up slowly, like every muscle in his body ached, and dislodging the oversized towel that Whiskey had used to cover him with.

He was… well, fit. But thin. He probably used the gym regularly, but not to bulk up. He had long muscles, the kind that were comfortable on very young bodies, and Whiskey suppressed a groan. God, please let this kid be legal, just to make that whole wood thing less disgusting.

Whiskey pressed the tablets into his hand and then gave him the water and watched as he obediently drank all sixteen ounces.

“Now I want you to go back to sleep,” Whiskey said sternly. “There will be another bottle here—drink it when you wake up, okay?”

The kid nodded, and again, that image of a kitten, a little white one with tousled fuzz on the top of its head and blue eyes. “Why does everything hurt?” he asked, his eyes so dark with pain they looked like bruises.

“Two reasons,” Whiskey told him shortly, taking the empty bottle for the recycling bin. “The first is that you were in a car wreck.” While the kid’s eyes got really big over that, Whiskey added the kicker. “The second is that you were drugged to the gills. Any idea what you took?”

The kid scrubbed his face with his hands, closing his eyes and making a sound like Whiskey had hit him. “Oh Jesus, fuck… shit, shit, shit, shit….” The kid collapsed on the bed and groaned, turning his head toward the wall.

“Kid?”

“Was I driving?” His voice was flat and emotionless.

“No.”

“Where’s my car?”

“In the bottom of the river. I would imagine by now someone’s noticed the hole in the guardrail and they’re probably hauling it out by now.”

Super Sock Man

Super Sock Man Safe Heart (Dreamspun Desires Book 102)

Safe Heart (Dreamspun Desires Book 102) Slow Pitch

Slow Pitch School of Fish

School of Fish Shades of Henry (The Flophouse Book 1)

Shades of Henry (The Flophouse Book 1) Ethan in Gold

Ethan in Gold Hidden Heart

Hidden Heart Familiar Demon

Familiar Demon Shortbread and Shadows

Shortbread and Shadows Silent Heart

Silent Heart Shortbread and Shadows (Dreamspun Beyond Book 41)

Shortbread and Shadows (Dreamspun Beyond Book 41) All the Rules of Heaven

All the Rules of Heaven Shades of Henry

Shades of Henry Homebird

Homebird Under the Rushes

Under the Rushes Fish on a Bicycle

Fish on a Bicycle Warm Heart

Warm Heart The Muscle

The Muscle The Bells of Times Square

The Bells of Times Square![Jack&Teague [& Katy] stories 1-5 Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/19/jackandteague_and_katy_stories_1-5_preview.jpg) Jack&Teague [& Katy] stories 1-5

Jack&Teague [& Katy] stories 1-5 Wounded, Volume 1

Wounded, Volume 1 Paint It Black

Paint It Black The Virgin Manny

The Virgin Manny Fall through Spring

Fall through Spring Clear Water

Clear Water If I Must Lane

If I Must Lane Stand by Your Manny

Stand by Your Manny Hiding the Moon

Hiding the Moon Freckles

Freckles Chase in Shadow

Chase in Shadow Sidecar

Sidecar Quickening, Volume 1

Quickening, Volume 1 Black John

Black John Bobby Green

Bobby Green Winter Ball

Winter Ball Hammer & Air

Hammer & Air A Few Good Fish

A Few Good Fish Dex in Blue

Dex in Blue Quickening, Volume 2

Quickening, Volume 2 A Fool and His Manny

A Fool and His Manny Manny Get Your Guy (Dreamspun Desires Book 37)

Manny Get Your Guy (Dreamspun Desires Book 37) Familiar Angel

Familiar Angel Bonfires

Bonfires The Locker Room

The Locker Room Rampant, Volume 2

Rampant, Volume 2 Left on St. Truth-Be-Well

Left on St. Truth-Be-Well A Solid Core of Alpha

A Solid Core of Alpha Red Fish, Dead Fish

Red Fish, Dead Fish Summer Lessons

Summer Lessons Country Mouse

Country Mouse City Mouse

City Mouse Turkey in the Snow

Turkey in the Snow Rampant, Volume 1

Rampant, Volume 1 Bitter Moon Saga

Bitter Moon Saga Candy Man

Candy Man Crocus

Crocus Green's Hill Werewolves, Volume 2

Green's Hill Werewolves, Volume 2 The Green's Hill Novellas

The Green's Hill Novellas